I want to tell you a story about Stephanie in 2013.

In 2013, Ben and I went to see Under the Skin, a sci-fi film starring Scarlett Johansson that was being praised for its evocative imagery and feminist undertones. I left that theater feeling extremely dissatisfied and upset about what I had seen. It wasn’t the eerie, sometimes terrifying imagery that did it (that part was great). It was the fact that throughout the whole movie Johansson had only said a handful of words. She had gone around carrying out the orders of these aliens who had taken seemingly male bodies without having any say in the matter until she broke and sought some means of escape from a life of kidnapping men.

“But that’s kind of the point, isn’t it?” Ben said (or said something like that). “It’s supposed to bring into focus the ways that women pursuing men can still be the will of the patriarchy.” And this was I think what the filmmakers intended. “But I already know it sucks to be a woman,” I said, becoming increasingly emotional. “I want stories that tell me how to make things better instead of just reminding me about how shitty everything is.”

At the time, I was working on my dissertation, which focuses on the role that personal narratives can play in adjusting how we view the world. My foundation assumption was something like this: When we encounter something we haven’t encountered before, we use the narratives we’ve heard to make sense of it. Consequently, the dominant narratives — the way that stories about a particular issue are usually structured — deeply influence how we receive and interpret all stories we hear.

An example: For a long time, the dominant narrative regarding abortion was that they were gotten by women who irresponsibly had sex outside of marriage and couldn’t be bothered to raise a child. We mostly assumed that it was teenagers that got abortions after youthful indiscretions. And if this is, in fact, the reality of it, citizens will make certain decisions about how best to deal with abortion, like abstinence-only sex ed in schools. But in the last few years, we’ve seen pro-choice groups deliberately trying to undermine that narrative by releasing statistics that show married women account for a significant number of abortions, including married women who already have other children. In 2013, New York Magazine ran a story of 21 women sharing their abortion experiences, and those women cited many different reasons for choosing to abort, like chronic medical issues, needing to care for other children, or being in bad relationships with the father. These different narratives suggest different approaches to policy — if it’s not teenagers doing this, then we need different solutions.

In my dissertation, I spend a lot of time thinking about common narratives about children with mental health issues and the ways that we judge real-life parents of mentally-ill children based on what we see via movies and television. I continue to believe that the media narratives that are available to us can deeply affect what we see as possible and/or probable in the real world. Which is why HBO’s new show Confederate seems like such a terrible idea to me. Many writers of color have already given detailed criticisms (like Roxane Gay and Ta-Nehisi Coates) about why they don’t want want to give the show a chance, even with two black writers on the team, and I believe that theirs are the voices that matter most in this debate. But I also want to express my rejection of the show as a white Southerner. You don’t have to look far to see that the people of the South have a hard time confronting their racist past and present. Even those who are well-intentioned often have no idea what to do with themselves, as Brad Paisley’s “Accidental Racist” shows; they struggle to find ways to express their identities as both Southerners and race-conscious individuals (because for some reason, Southerners need to express their solidarity as Southerners in ways that Midwesterners, for example, don’t; I blame the rest of the country for using the South as a dumping ground for making themselves feel less racist/homophobic/ignorant/etc.). I’m disappointed by the basic premise of Confederate because it offers nothing new for us as white Southerners of conscience, no new ways to imagine what a truly equitable society looks like and how we can enact it. An “alternate history” is allowed to remain “fantasy” in our minds, not necessarily forcing viewers to confront their everyday habits and practices. Not to mention it perpetuates the misconception that the South is the root of all racism, instead of the responsibility being shared by all of us who have benefited from white privilege.

I’m not saying that art (including television and movies) shouldn’t be a vehicle for cultural criticism, but there comes a point where criticism is not enough. We need radically new stories because they offer us radically new ways to imagine our relationships to others, and this includes our relationships to and among minority groups. Confederate gives us nothing new to work with.

Today I’m taking a look at John Scalzi’s 2005 novel Old Man’s War, which was nominated for a Hugo in 2006. This was my first Scalzi, though I’ve been well-aware of his Twitter activity for a while, and I was excited to jump into one of his novels. My husband and I listened to it on audio book during our summer road trip, and in this post, I’ll be recounting some of our thoughts and reactions as we were listening.

Today I’m taking a look at John Scalzi’s 2005 novel Old Man’s War, which was nominated for a Hugo in 2006. This was my first Scalzi, though I’ve been well-aware of his Twitter activity for a while, and I was excited to jump into one of his novels. My husband and I listened to it on audio book during our summer road trip, and in this post, I’ll be recounting some of our thoughts and reactions as we were listening. Case in point: At one point, a new recruit joins John’s unit, a man who used to be a U.S. member of congress. Even before he’s seen his first battle, the politician goes about telling anyone who will listen about how the Colonial Union deploys the CDF too frequently without first searching for diplomatic solutions. The politician has been researching the alien race his unit is slotted to meet in combat, the Whaidian, and argues that they are an artistic, communally-oriented society with whom the Colonial Union could arrange a mutually beneficial treaty if they only tried. Other members of the unit, especially the veterans, write the politician off as ignorant and idealistic (and it doesn’t help that he takes the pedantic, condescending tone of old, white, male politicians everywhere), and no one is surprised when he attempts to talk the Whaidian and is brutally killed. At the same time, John’s current superior officer notes that the politician was right – that troops are deployed too quickly and diplomatic solutions are never sought. She argues, however, that the best way to enact change is for individuals to work within the system by climbing the ranks until they are the ones giving the orders. Her ambitions are cut short with her own death.

Case in point: At one point, a new recruit joins John’s unit, a man who used to be a U.S. member of congress. Even before he’s seen his first battle, the politician goes about telling anyone who will listen about how the Colonial Union deploys the CDF too frequently without first searching for diplomatic solutions. The politician has been researching the alien race his unit is slotted to meet in combat, the Whaidian, and argues that they are an artistic, communally-oriented society with whom the Colonial Union could arrange a mutually beneficial treaty if they only tried. Other members of the unit, especially the veterans, write the politician off as ignorant and idealistic (and it doesn’t help that he takes the pedantic, condescending tone of old, white, male politicians everywhere), and no one is surprised when he attempts to talk the Whaidian and is brutally killed. At the same time, John’s current superior officer notes that the politician was right – that troops are deployed too quickly and diplomatic solutions are never sought. She argues, however, that the best way to enact change is for individuals to work within the system by climbing the ranks until they are the ones giving the orders. Her ambitions are cut short with her own death. After reading something (relatively) old, I moved on to something (relatively) new: Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2012 novel 2312, which was nominated for the 2013 Hugo and won the 2013 Nebula. It was also honored listed for the 2012 James Tiptree, Jr. Award, given to works that explore and expand our understandings of gender.

After reading something (relatively) old, I moved on to something (relatively) new: Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2012 novel 2312, which was nominated for the 2013 Hugo and won the 2013 Nebula. It was also honored listed for the 2012 James Tiptree, Jr. Award, given to works that explore and expand our understandings of gender.

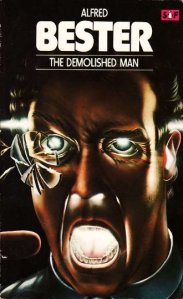

After a very, very long vacation, Speculative Rhetoric is back, this time with even more ambitious reading plans. I’ve decided to mark the occasion of me throwing myself back into the world of reading and writing about speculative fiction by reviewing the very first winner of the Hugo Award, Alfred Bester’s 1953 novel The Demolished Man. In the course of his varied career, Bester wrote for television, radio, and comics (he created DC villain Solomon Grundy) as well as science fiction short stories and novels.

After a very, very long vacation, Speculative Rhetoric is back, this time with even more ambitious reading plans. I’ve decided to mark the occasion of me throwing myself back into the world of reading and writing about speculative fiction by reviewing the very first winner of the Hugo Award, Alfred Bester’s 1953 novel The Demolished Man. In the course of his varied career, Bester wrote for television, radio, and comics (he created DC villain Solomon Grundy) as well as science fiction short stories and novels. As I was preparing to write this post, I found this quote from Bester’s essay “My Affair with Science Fiction” describing the events that followed his first published story winning an amateur story competition in Thrilling Wonder Stories: “Two editors on the staff […] took an interest in me, I suspect mostly because I’d just finished reading and annotating Joyce’s Ulysses and would preach it enthusiastically without provocation, to their great amusement.” I was struck by this statement because I had described The Demolished Man as a science fiction version of British modernism, chocked full of awkward Freudianism, with the plot hinging on Reich’s oedipal compulsions (spoiler alert: D’Courtney is Reich’s father, though Reich seems to have repressed his knowledge of this fact to the point of unconsciously misreading messages sent by the other man). Sections of the novel are devoted to Lincoln Powell diving into the psyche of D’Courtney’s daughter Barbara who, after becoming catatonic as a result of witnessing her father’s murder, is regressed to an infant state to mentally grow up once more and thereby come to cope with the trauma – a plot device that allows the electra complex to make an appearance as Barbara and Lincoln fall in love with each other as he raises her out of infancy and into adulthood. It’s actually this Freudianism that takes the misogyny of the era from irritating to downright creepy for me; while Lincoln has a grown woman with whom he’s developed a close friendship (Mary) who loves and is in love with him, he wants the woman who he raised through childhood and adolescents (although it appears that Mary did most of the work).

As I was preparing to write this post, I found this quote from Bester’s essay “My Affair with Science Fiction” describing the events that followed his first published story winning an amateur story competition in Thrilling Wonder Stories: “Two editors on the staff […] took an interest in me, I suspect mostly because I’d just finished reading and annotating Joyce’s Ulysses and would preach it enthusiastically without provocation, to their great amusement.” I was struck by this statement because I had described The Demolished Man as a science fiction version of British modernism, chocked full of awkward Freudianism, with the plot hinging on Reich’s oedipal compulsions (spoiler alert: D’Courtney is Reich’s father, though Reich seems to have repressed his knowledge of this fact to the point of unconsciously misreading messages sent by the other man). Sections of the novel are devoted to Lincoln Powell diving into the psyche of D’Courtney’s daughter Barbara who, after becoming catatonic as a result of witnessing her father’s murder, is regressed to an infant state to mentally grow up once more and thereby come to cope with the trauma – a plot device that allows the electra complex to make an appearance as Barbara and Lincoln fall in love with each other as he raises her out of infancy and into adulthood. It’s actually this Freudianism that takes the misogyny of the era from irritating to downright creepy for me; while Lincoln has a grown woman with whom he’s developed a close friendship (Mary) who loves and is in love with him, he wants the woman who he raised through childhood and adolescents (although it appears that Mary did most of the work).

_by_Veronica_Roth_US_Hardcover_2011.jpg) The World: Set in post-apocalyptic Chicago, Divergent presents readers with a society divided based on what qualities or ideologies individuals hold most dear. The five factions — Abnegation, Candor, Dauntless, Erudite, and Amity — comprise people who have opted to live their lives committed to their faction’s guiding principle. Amity, commited to kindness and harmony, lives outside of town and tends the agricultural and water purification needs of the city, while Erudite, striving after knowledge, focus on scientific developments to keep food and water coming. Dauntless, whose guiding principle is bravery, take care of protecting the borders (though against what, no one knows). Abnegation, committed to selflessness, manages all goverment affairs (based on the assumption that power should be given to those who do not want it), while Candor, who value honesty, work to prevent corruption. Factions are supposed to be prized more highly than family ties, as an individual’s faction tells her who she truly is, and others can expect her to act in a predictable way based on her faction.

The World: Set in post-apocalyptic Chicago, Divergent presents readers with a society divided based on what qualities or ideologies individuals hold most dear. The five factions — Abnegation, Candor, Dauntless, Erudite, and Amity — comprise people who have opted to live their lives committed to their faction’s guiding principle. Amity, commited to kindness and harmony, lives outside of town and tends the agricultural and water purification needs of the city, while Erudite, striving after knowledge, focus on scientific developments to keep food and water coming. Dauntless, whose guiding principle is bravery, take care of protecting the borders (though against what, no one knows). Abnegation, committed to selflessness, manages all goverment affairs (based on the assumption that power should be given to those who do not want it), while Candor, who value honesty, work to prevent corruption. Factions are supposed to be prized more highly than family ties, as an individual’s faction tells her who she truly is, and others can expect her to act in a predictable way based on her faction. The Plot: We meet our protagonist, Tris, at the age of sixteen, right before she will choose her faction. Raised in Abnegation, Tris attends school with children from all factions where, at the end of their education, they are put through simulations to determine which faction they are most suited for. When Tris undergoes her simulation, she discovers that she is “divergent,” or suitable for multiple factions. Additionally, she is aware during simulations in ways that other are not. However, this ability might get her killed as divergent members of the population often disappear or die under mysterious circumstances once their divergence is discovered. While she is suitable for either Abnegation, Erudite, or Dauntless, Tris opts to join the Dauntless faction and spends the next few weeks training with other recruits. Though small and relatively weak when she begins, Tris rises through the ranks to graduate top of her initiation class. In the meantime, she also learns some family secrets and falls in love with one of her teachers, Four (so-called because he only has four fears, an highly valued characteristic in a faction that values bravery). However, the night after her graduation, all of Dauntless falls under a simulation (with the exception of a few key leaders) and begin invading the Abnegation part of the city, killing leaders and resistors along the way. As Four and Tris are both divergent and thus aware, it falls to them to do what they can to stop the massacre.

The Plot: We meet our protagonist, Tris, at the age of sixteen, right before she will choose her faction. Raised in Abnegation, Tris attends school with children from all factions where, at the end of their education, they are put through simulations to determine which faction they are most suited for. When Tris undergoes her simulation, she discovers that she is “divergent,” or suitable for multiple factions. Additionally, she is aware during simulations in ways that other are not. However, this ability might get her killed as divergent members of the population often disappear or die under mysterious circumstances once their divergence is discovered. While she is suitable for either Abnegation, Erudite, or Dauntless, Tris opts to join the Dauntless faction and spends the next few weeks training with other recruits. Though small and relatively weak when she begins, Tris rises through the ranks to graduate top of her initiation class. In the meantime, she also learns some family secrets and falls in love with one of her teachers, Four (so-called because he only has four fears, an highly valued characteristic in a faction that values bravery). However, the night after her graduation, all of Dauntless falls under a simulation (with the exception of a few key leaders) and begin invading the Abnegation part of the city, killing leaders and resistors along the way. As Four and Tris are both divergent and thus aware, it falls to them to do what they can to stop the massacre. On the other hand, I really love that the super power of this world is, simply put, critical thinking skills. Tris, Four, and the other divergent are special because they can see the world around them from multiple viewpoints and take on multiple, sometimes conflicting, ideologies. And the fact that something as simple as taking on multiple perspectives can be a super power is a sharp warning about one possible future for us. In the subsequent novels (I’m currently listening to second of the trilogy, Insurgent, on audiobook), Roth explains that the faction system keeps people manageable by making them predictable; that is, keeping people committed to a single ideological framework is good for those in power (or those who are trying to come into power). And that reader can see each faction as having positive goals sharpens this critique, demonstrating that even values that we can agree are good are dangerous when they become a single focus. Of course, this kind of statement has been made frequently before. We’re familiar with the stories of those who pursue knowledge at the cost of human life, and we know why absolute honesty is not always the best policy. What Roth’s novel adds to this conversation is an illustration of how proponents of these values may interact. And while Tris’s rhetorical skills are not necessarily at the forefront of this first novel, I think they will become more important in the rest of the trilogy as she negotiates among various groups to stop a wannabe dictator from taking power.

On the other hand, I really love that the super power of this world is, simply put, critical thinking skills. Tris, Four, and the other divergent are special because they can see the world around them from multiple viewpoints and take on multiple, sometimes conflicting, ideologies. And the fact that something as simple as taking on multiple perspectives can be a super power is a sharp warning about one possible future for us. In the subsequent novels (I’m currently listening to second of the trilogy, Insurgent, on audiobook), Roth explains that the faction system keeps people manageable by making them predictable; that is, keeping people committed to a single ideological framework is good for those in power (or those who are trying to come into power). And that reader can see each faction as having positive goals sharpens this critique, demonstrating that even values that we can agree are good are dangerous when they become a single focus. Of course, this kind of statement has been made frequently before. We’re familiar with the stories of those who pursue knowledge at the cost of human life, and we know why absolute honesty is not always the best policy. What Roth’s novel adds to this conversation is an illustration of how proponents of these values may interact. And while Tris’s rhetorical skills are not necessarily at the forefront of this first novel, I think they will become more important in the rest of the trilogy as she negotiates among various groups to stop a wannabe dictator from taking power. Steph Swainston’s debut novel The Year of Our War was published in 2004 and introduces readers to the Fourlands, a world inhabited by three races of humanoids: the Awaians, a winged race; the Rhydannes, a small cat-like race from the mountains, and the regular old humans. A fourth race, the Insects, has taken over the northern portion of the continent and continues to push south, destroying towns and turning them into Paperlands. The novel follows Jant Shira, a Rhydanne-Awaian hybrid whose light body and wings allow him to fly. Jant is a member of the Circle, a group of immortals ruled by Emperor San and charged with protecting the Fourlands. These immortals do not age or die from natural causes, though they can be killed in battle, extreme weather, etc. Jant is the Messenger of the Emperor, called “Comet,” and is addicted to a drug that allows him to access another world called the Shift. Jant finds himself embroiled in the internal intrigue of the Circle while the Insects sweep across the continent and the Emperor threatens to revoke his immortality if Jant can’t provide some answers.

Steph Swainston’s debut novel The Year of Our War was published in 2004 and introduces readers to the Fourlands, a world inhabited by three races of humanoids: the Awaians, a winged race; the Rhydannes, a small cat-like race from the mountains, and the regular old humans. A fourth race, the Insects, has taken over the northern portion of the continent and continues to push south, destroying towns and turning them into Paperlands. The novel follows Jant Shira, a Rhydanne-Awaian hybrid whose light body and wings allow him to fly. Jant is a member of the Circle, a group of immortals ruled by Emperor San and charged with protecting the Fourlands. These immortals do not age or die from natural causes, though they can be killed in battle, extreme weather, etc. Jant is the Messenger of the Emperor, called “Comet,” and is addicted to a drug that allows him to access another world called the Shift. Jant finds himself embroiled in the internal intrigue of the Circle while the Insects sweep across the continent and the Emperor threatens to revoke his immortality if Jant can’t provide some answers. K. J. Bishop’s first novel, The Etched City, appeared in 2003 and is her only novel to date. I had read a couple of her short stories, most notably “The Art of Dying” from the Vandermeer’s The New Weird anthology, so I was somewhat prepared for Bishop’s world of gunslingers and duelists, artists and prostitutes. At the same time, The Etched City is a novel that I can’t get out of my head and that I have trouble explaining to others when I try.

K. J. Bishop’s first novel, The Etched City, appeared in 2003 and is her only novel to date. I had read a couple of her short stories, most notably “The Art of Dying” from the Vandermeer’s The New Weird anthology, so I was somewhat prepared for Bishop’s world of gunslingers and duelists, artists and prostitutes. At the same time, The Etched City is a novel that I can’t get out of my head and that I have trouble explaining to others when I try. In many ways, this novel felt less like a narrative and more like a series of very striking moments; Bishop’s language was frequently visceral and vivid, but I had trouble seeing how things really fit together over time. I was even a little disappointed that we spent so little time with Raule when I found her much more interesting that Gwynn; once the two reach the city of Ashamoil, we become deeply embroiled in the goings-on of Gwynn and his employer, with occasional glimpses at what Raule is doing. One thing that I did really like, though, is the way that magic is introduced in the novel. I really like when magic isn’t normally part of a world and the characters have to come to terms with extraordinary events just as readers do. Add in the fact that several characters are also alcoholics and drug users, and it makes it hard to tell when something extraordinary is actually happening and when it’s only happening in the mind of a character. As such, the first few magical events are easily passed off as misperception or hallucination, but it slowly becomes clear that not all things are as they seem.

In many ways, this novel felt less like a narrative and more like a series of very striking moments; Bishop’s language was frequently visceral and vivid, but I had trouble seeing how things really fit together over time. I was even a little disappointed that we spent so little time with Raule when I found her much more interesting that Gwynn; once the two reach the city of Ashamoil, we become deeply embroiled in the goings-on of Gwynn and his employer, with occasional glimpses at what Raule is doing. One thing that I did really like, though, is the way that magic is introduced in the novel. I really like when magic isn’t normally part of a world and the characters have to come to terms with extraordinary events just as readers do. Add in the fact that several characters are also alcoholics and drug users, and it makes it hard to tell when something extraordinary is actually happening and when it’s only happening in the mind of a character. As such, the first few magical events are easily passed off as misperception or hallucination, but it slowly becomes clear that not all things are as they seem. This unfolding of the magical world corresponds with one of the dominant themes of the novel, that of metamorphosis. A wide number of items and events in the novel are related to this theme: eggs, cocoons, fetuses, lobotomies, flowers, etc. Contrasted with this are moments of stasis, such as the poor of the city who have little to no mobility or the “primitive” people that Gwynn’s employer holds in a never-ending civil war for the sake of his slave trade. The Rev seems to be a nexus for these themes in that he finds himself able to produce many kinds of small magic, but ultimately he is stuck with his own guilt and self-doubt and romantic fantasies about young, nubile women.

This unfolding of the magical world corresponds with one of the dominant themes of the novel, that of metamorphosis. A wide number of items and events in the novel are related to this theme: eggs, cocoons, fetuses, lobotomies, flowers, etc. Contrasted with this are moments of stasis, such as the poor of the city who have little to no mobility or the “primitive” people that Gwynn’s employer holds in a never-ending civil war for the sake of his slave trade. The Rev seems to be a nexus for these themes in that he finds himself able to produce many kinds of small magic, but ultimately he is stuck with his own guilt and self-doubt and romantic fantasies about young, nubile women. I’ve been spending my summer reading time working on books for my SLA (Specialized Literature Area) Exam, which is focusing on the New Weird (hence all the China Miéville reviews recently). However, I was starting to get frustrated and overwhelmed with the project and allowed myself a “real” summer reading book, something that wasn’t geared toward any project or exam I’m currently working on. I’m not sure how I picked Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, but I got my boyfriend to bring it home from the library and read the first half of the book in about two days. The second half took the rest of the week, but I can now turn back to my exam reading feeling somewhat refreshed and ready to look at the New Weird with new eyes.

I’ve been spending my summer reading time working on books for my SLA (Specialized Literature Area) Exam, which is focusing on the New Weird (hence all the China Miéville reviews recently). However, I was starting to get frustrated and overwhelmed with the project and allowed myself a “real” summer reading book, something that wasn’t geared toward any project or exam I’m currently working on. I’m not sure how I picked Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, but I got my boyfriend to bring it home from the library and read the first half of the book in about two days. The second half took the rest of the week, but I can now turn back to my exam reading feeling somewhat refreshed and ready to look at the New Weird with new eyes. What I found most interesting as I was reading this book was the way my loyalties changed throughout. The characters in this novel are well-constructed; I both hated and sympathized with almost every one of them throughout the course of the narrative, which I always take as the sign of good characters (this is one of the main reasons I love Battlestar Galactica). I often perceived the women of Avalon as shrewish as they insisted Arthur maintain the status of Goddess worship alongside Christianity, like they were not acknowledging the complicated materialities of Arthur’s position, how he must manage so many people in order to keep peace. I tended to side with the Merlins, Taliesin and Kevin, who argued for plurality: that all Gods are one God no matter what name he is called by, and that the time of Avalon had passed, so the best thing to do was to infuse Christianity with as much of druidism and Goddess worship as possible. Thus, Kevin steals the Holy Regalia of the Goddess in order for it to be in the world, incorporated into Christian worship. What brought me back to the side of Avalon, over and over again, was the reminder that women were getting really and truly hosed under the brand of Christianity that was coming from Camelot (there were other groups of Christians that were finding themselves persecuted for accepting the pluralistic view that Taliesin preached; Kevin is something of a different story, I think). I think that the scene between Gwydion and Niniane toward the end of the novel is very telling, as Gwydion, who does not ascribe to Christianity seeks to police Gwenhwyfar’s sexual liasons in the same way the Christian priests would, but Niniane refuses to participate and Gwydion kills her. The new system of gender hierarchy is not strictly a Christian one, but it is pervasive and unstoppable.

What I found most interesting as I was reading this book was the way my loyalties changed throughout. The characters in this novel are well-constructed; I both hated and sympathized with almost every one of them throughout the course of the narrative, which I always take as the sign of good characters (this is one of the main reasons I love Battlestar Galactica). I often perceived the women of Avalon as shrewish as they insisted Arthur maintain the status of Goddess worship alongside Christianity, like they were not acknowledging the complicated materialities of Arthur’s position, how he must manage so many people in order to keep peace. I tended to side with the Merlins, Taliesin and Kevin, who argued for plurality: that all Gods are one God no matter what name he is called by, and that the time of Avalon had passed, so the best thing to do was to infuse Christianity with as much of druidism and Goddess worship as possible. Thus, Kevin steals the Holy Regalia of the Goddess in order for it to be in the world, incorporated into Christian worship. What brought me back to the side of Avalon, over and over again, was the reminder that women were getting really and truly hosed under the brand of Christianity that was coming from Camelot (there were other groups of Christians that were finding themselves persecuted for accepting the pluralistic view that Taliesin preached; Kevin is something of a different story, I think). I think that the scene between Gwydion and Niniane toward the end of the novel is very telling, as Gwydion, who does not ascribe to Christianity seeks to police Gwenhwyfar’s sexual liasons in the same way the Christian priests would, but Niniane refuses to participate and Gwydion kills her. The new system of gender hierarchy is not strictly a Christian one, but it is pervasive and unstoppable. Which leads to my complaints about the end of the novel. Morgaine’s discovery of the Goddess in the small chapel dedicated to Mary and the simple joy that nuns of Glastonbury experience in their lives represents for her that the Goddess lives on in the world in a new form, that her work was not in vain, and that she should have listened to Kevin all along. At the same time, I’m infuriated that Morgaine is okay with the sexual rights of women virtually disappearing, and I’m dissatisfied that the novel’s ending suggests that all has worked out for the best. A pluralist society is not really pluralist when not everyone accepts and acknowledges the pluralism, which is exactly what Morgaine and the women of Avalon argue for when they ask Arthur to protect Goddess worship in his kingdom.

Which leads to my complaints about the end of the novel. Morgaine’s discovery of the Goddess in the small chapel dedicated to Mary and the simple joy that nuns of Glastonbury experience in their lives represents for her that the Goddess lives on in the world in a new form, that her work was not in vain, and that she should have listened to Kevin all along. At the same time, I’m infuriated that Morgaine is okay with the sexual rights of women virtually disappearing, and I’m dissatisfied that the novel’s ending suggests that all has worked out for the best. A pluralist society is not really pluralist when not everyone accepts and acknowledges the pluralism, which is exactly what Morgaine and the women of Avalon argue for when they ask Arthur to protect Goddess worship in his kingdom..jpg/200px-TheScar(1stEd).jpg) China Mieville’s 2002 novel The Scar is a loose sequel to Perdido Street Station, set in Bas-Lag several months after the events of the previous novel. Like its predecessor, The Scar won the British Fantasy Award, and it was nominated for the Arthur C. Clark, the Philip K. Dick, and the Hugo awards.

China Mieville’s 2002 novel The Scar is a loose sequel to Perdido Street Station, set in Bas-Lag several months after the events of the previous novel. Like its predecessor, The Scar won the British Fantasy Award, and it was nominated for the Arthur C. Clark, the Philip K. Dick, and the Hugo awards. Bellis Coldwine was an interesting heroine. I found her immediately appealing because of the way she carefully considers her options in various situations: “Bellis sat still. She was not intimidated by this man, but she had no power over him, none at all. She tried to work out what was most likely to engage his sympathy, make him acquiesce” (14-5). In the same way, she considers how others, especially the Lovers, are using language to persuade others. She is, in short, a rhetorician, weighing her available means of persuasion and analyzing the means of others throughout the novel as she navigates her way back to New Crozubon. If you read my posts about Neal Stephenson’s Anathem, Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea novels, and Kristin Cashore’s Graceling, you know that representations of rhetors and rhetoric in fiction is one of my primary concerns, and I really consider The Scar a win for rhetoric.

Bellis Coldwine was an interesting heroine. I found her immediately appealing because of the way she carefully considers her options in various situations: “Bellis sat still. She was not intimidated by this man, but she had no power over him, none at all. She tried to work out what was most likely to engage his sympathy, make him acquiesce” (14-5). In the same way, she considers how others, especially the Lovers, are using language to persuade others. She is, in short, a rhetorician, weighing her available means of persuasion and analyzing the means of others throughout the novel as she navigates her way back to New Crozubon. If you read my posts about Neal Stephenson’s Anathem, Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea novels, and Kristin Cashore’s Graceling, you know that representations of rhetors and rhetoric in fiction is one of my primary concerns, and I really consider The Scar a win for rhetoric. I kept thinking, though, as I was reading, that this novel seemed to be less political than Perdido Street Station; while the social organization of Armada is interesting, it also seems very tied to a particular physical organization and, consequently, has few implications for “real life”. I’ve decided, though, that this novel is just as political, but in a different way; rather than being a story about people getting together to do something, this is a story about not having agency. Bellis realizes at the end of the adventure (for lack of a better word) that she had been a tool the whole time, first of one man, then another. While she did influence the events that happened, she could not do so in any kind of informed or strategic way, because she never had enough information to really know what she was doing, even when she was very good at doing it. And Bellis was very good at persuading others, manipulating some events to (what she thought was) her advantage. When Bellis realizes that she had no real agency in the events, though, she simply accepts this, since her “service” does ultimately earn her a ride back to New Crozubon (so does that count as agency? I feel so conflicted…). It is Bellis’s reaction to this revelation that made me feel a bit, well, cold toward her; I found that I had been pulled into sympathizing with Bellis more than maybe I should have because I immediately grabbed onto what I saw as our commonalities (“You’re a rhetorician?! I’m a rhetorician too! We should hang out sometime!”). Her utilitarian reaction to being a pawn, though, rankles my sense of justice even as it caters to my cynicism. At the same time, the ambiguity I feel toward her now (she can be a right bitch at moments) makes her even better as a character, and I can think of few female fantasy characters written by men who have impressed me this much.

I kept thinking, though, as I was reading, that this novel seemed to be less political than Perdido Street Station; while the social organization of Armada is interesting, it also seems very tied to a particular physical organization and, consequently, has few implications for “real life”. I’ve decided, though, that this novel is just as political, but in a different way; rather than being a story about people getting together to do something, this is a story about not having agency. Bellis realizes at the end of the adventure (for lack of a better word) that she had been a tool the whole time, first of one man, then another. While she did influence the events that happened, she could not do so in any kind of informed or strategic way, because she never had enough information to really know what she was doing, even when she was very good at doing it. And Bellis was very good at persuading others, manipulating some events to (what she thought was) her advantage. When Bellis realizes that she had no real agency in the events, though, she simply accepts this, since her “service” does ultimately earn her a ride back to New Crozubon (so does that count as agency? I feel so conflicted…). It is Bellis’s reaction to this revelation that made me feel a bit, well, cold toward her; I found that I had been pulled into sympathizing with Bellis more than maybe I should have because I immediately grabbed onto what I saw as our commonalities (“You’re a rhetorician?! I’m a rhetorician too! We should hang out sometime!”). Her utilitarian reaction to being a pawn, though, rankles my sense of justice even as it caters to my cynicism. At the same time, the ambiguity I feel toward her now (she can be a right bitch at moments) makes her even better as a character, and I can think of few female fantasy characters written by men who have impressed me this much.